Burn Baby, Burn…

“Satisfaction, came in the chain reaction…I couldn’t get enough, ‘till I had to self-destruct”. The Trammps, Disco Inferno.

Recently, CBInsights published a report detailing 339 startup failure post-mortems. One of their key findings was that 70% of tech startups after raising on average $1.3m failed around 20 months. Turns out the two big killers of startups were “No Market Need”, and “Running out of Cash”.

One founder wrote : “We have run out of time and have not been able to secure funding for the company… I will never be able to forgive myself for not taking action sooner.”

This highlights a remarkably difficult challenge that founders face on a daily basis:

Managing Burn effectively.

“Cut, Burn and Survive” were the key messages we all gave our founders over the past few months. But, this leads one to ask: What is responsible burn? Does it mean cutting your payroll? Cutting down on Nespresso pods? Below are some pointers and thoughts:

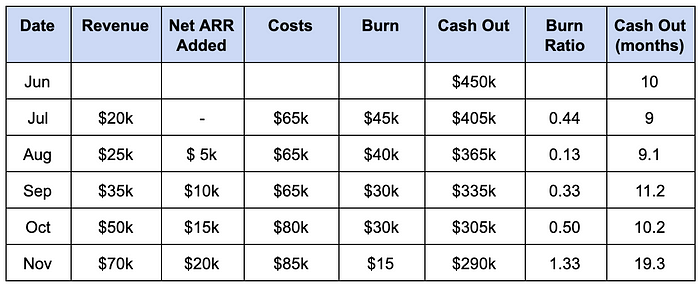

Burn = Revenue — Cash Spent on all costs and capital expenses.

Each additional dollar you spend, and every additional hire you make, affects your burn and hence the “cash out” date (the date your cash is $0). Your cash out is determined by taking your available cash less the closing costs of the company and dividing the result by your current Burn.

As an example, if you have $500,000 cash on hand, to close the company you need $50,000, and you are burning $45,000 per month, then ($500,000 — $50,000) / $45,000 = 10 months of runway.

As Paul Graham likes to say, if you can just avoid dying, you get rich. Avoiding death means managing your Burn effectively.

A Key to understanding Burn: Net ARR Added / Monthly Burn.

This formula gives you direct insight into how much additional breathing room each additional dollar gets you. Taking the above example further:

In the above example, the burn ratio steadily increases and the cash out increases with it. This is despite the fact that we’ve accounted for adding more costs into the business. A few observations:

- The business is growing at a good pace (though its still very early) and on this basis can break even in as little as 3 months. With a cash out of 19 months, one can afford to take more risk, hire additional people and market/advertise more.

- The added costs are leading to a greater ARR — now we are onto something!

- The burn ratio increasing is an important indicator. Anything over 1.0 is fantastic. Anything under 0.4 is probably not.

The most obvious ways to burn money are hiring more people and spending on marketing.

Our advice to early stage founders on hiring is clear: don’t do it if you don’t have to. Once the cash hits the bank, founders feel a tremendous amount of pressure to hire quickly — fuelled by mantras like “move fast and break things”. Moving fast doesn’t always mean hiring fast! It’s important to evaluate your needs down to the task level before making a hiring decision. Too often do founders hire a “VP of X” when the same job could have been done by a hungry junior hire.

For every additional dollar spent, ask yourself: is this giving me more room to breathe? This is where gross margins are key — how hard do you need to work per $ of cash flow i.e. how much of every dollar earned can be recycled for growth?

Gross Margin – Not all revenues are created equal!

One of the most important growth factors that entrepreneurs overlook are gross margins. Higher gross margin means that for each additional dollar of revenue, more money gets to be spent on building the business. In the long term, this means less dilution for the founder — revenue is the best form of equity, as long as there is good gross margins and/or cash flows.

In the above table you’ll see that in July, for every dollar of revenue, the Company spent $ 3.25. By November, for every $1 of revenue the company spent $1.13 — an indicator that the business has good gross margins.

Simply put, if you have $20k of revenue per month and 5% gross margins, then you are effectively ”increasing” your pool of cash by $1k. But if you are a typical software SaaS business, your margin should be 80%+ i.e. you are adding $16k every month to the pool of cash — that creates a completely different business.

Designing your business model with all of this in mind makes your chances of success greater, and reduces the chances that your survival / dilution will be at the mercy of investors at your next financing round.

Revenue often costs too much.

One will often face a tradeoff between cash flow paid annually at a discount and higher revenues from customers.

Revenue is Vanity, Profit is Sanity …. and Cash is Reality!

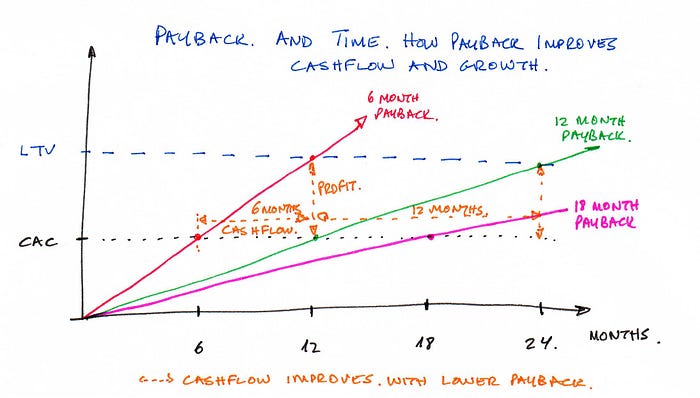

Cash upfront helps fuel growth which has a multiplier effect — especially if the business has high gross margins.

Investing every dollar into building the product and acquiring customers is great, but what about hiring the account managers needed to satisfy them and reduce churn? You need to plan ahead, and hire customer success/support teams to ensure you keep the revenues you’ve generated as it’s much easier to lose a customer than to gain one.

Payback period and CAC are Key.

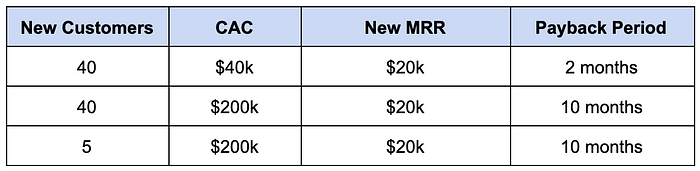

Have a look at the 3 examples in the table below (measured per month):

The first example is terrific. A CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) of $1,000 per customer with a payback in two months.

The second example is pretty good and at a level most SaaS software companies would be very happy with — same number of customers, more CAC spend, yet its paid back in 10 months — here you need to consider lifetime value LTV and invest more in retaining the customer, hence more costs down the line, otherwise your ROI is not great.

The third one, clearly an enterprise play, leaves very few options if anything goes wrong (or long). Here you have less diversity in customers i.e. 5 vs. 40 so you need to invest just as much in retaining them if not more, and you need to ensure the LTV is much longer period.

SaaS companies with repayment periods greater than 18 months should go back to the drawing board and figure out how to reduce the payback period.

Advice: If you can discount by one month and charge annually in advance, you can make that money work for you over and over again. But you can only do this at scale if your Gross Margin is big (ie 70%+), and your Payback Period is lower i.e. a year or less. You’ll even find plenty of financial institutions willing to fund your CAC spend and thus give you even greater ROI!

Selling a dollar for 90 cents?

Too many startups fail to build their businesses with unit economics in mind, and think that it’s something that can be figured out once they’ve “scaled up”. The path to positive unit economics should be created early.

In the long run, positive unit economics will enable you to fuel growth — both from the reinvestment of each additional early revenue dollar, and from investors who will be willing to provide capital at reasonable valuations.

Scaling your startup with terrible unit economics will get you larger revenue but with the accompanying bad habits, systems and overhead, which in turn will give you a much harder problem to solve. Spend longer figuring this out before scaling with dollars.

Related Resources

The Rise of Mission-Driven Founders: Beyond Profit to Purpose

How should I reach out to a VC for the first time?